Machine Learning and Wine

Who says wine can’t be paired with Machine Learning?

Summary:

Ever wondered what would happen if we combined machine learning and wine together? In this fun little project, we attempt to use support vector machines using R to classify the quality of various red and white Portuguese “Vinho Verde” wines on a scale of 1-10 (1 being the worst to 10 being the best) using only the physiochemical properties of the wines. The full project involved using both support vector machines and neural networks to compare the differences in performance. To view more the project in it’s entirety, click on the github badge above. However, for the purposes of this post, we will focus primarily on how to deploy support vector machines.

Data:

The Wine Dataset can be found on the UCI Machine Learning Repository and includes 6,497 observations with 12 variables in total. In order to train the models, the data is split into three datasets using random sampling methods: Training, Validation, and Testing.

Step 1: Load Packages and Read in the Data

Let’s begin by the loading the necessary packages for this project.

library(ggplot2)

library(tidyverse)

library(kernlab)

library(e1071)

library(caret)

As a quick summary of each package, ggplot2 is used for visualization, tidyverse is a data cleaning tool, kernlab package contains multiple kernel based machine learning models including the support vector model used in this project, and the caret package contains miscellaneous functions for training and plotting classification and regression models.

Next, we read in the data.

white_wine <- read.csv("winequality-white.csv", sep = ";")

red_wine <- read.csv("winequality-red.csv", sep = ";")

Step 2: Inspect the data

In order to gain a better understanding of the data we are working with, it is important to explore the data. What type of data are we working with? Are there any missing values? How many observations are we working with? These questions provide a starting point when beginning a machine learning project.

The str function provides a quick and easy way to get a sense of the data.

str(white_wine)

'data.frame': 4898 obs. of 12 variables:

$ fixed.acidity : num 7 6.3 8.1 7.2 7.2 8.1 6.2 7 6.3 8.1 ...

$ volatile.acidity : num 0.27 0.3 0.28 0.23 0.23 0.28 0.32 0.27 0.3 0.22 ...

$ citric.acid : num 0.36 0.34 0.4 0.32 0.32 0.4 0.16 0.36 0.34 0.43 ...

$ residual.sugar : num 20.7 1.6 6.9 8.5 8.5 6.9 7 20.7 1.6 1.5 ...

$ chlorides : num 0.045 0.049 0.05 0.058 0.058 0.05 0.045 0.045 0.049 0.044 ...

$ free.sulfur.dioxide : num 45 14 30 47 47 30 30 45 14 28 ...

$ total.sulfur.dioxide: num 170 132 97 186 186 97 136 170 132 129 ...

$ density : num 1.001 0.994 0.995 0.996 0.996 ...

$ pH : num 3 3.3 3.26 3.19 3.19 3.26 3.18 3 3.3 3.22 ...

$ sulphates : num 0.45 0.49 0.44 0.4 0.4 0.44 0.47 0.45 0.49 0.45 ...

$ alcohol : num 8.8 9.5 10.1 9.9 9.9 10.1 9.6 8.8 9.5 11 ...

$ quality : int 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 ...

str(red_wine)

'data.frame': 1599 obs. of 12 variables:

$ fixed.acidity : num 7.4 7.8 7.8 11.2 7.4 7.4 7.9 7.3 7.8 7.5 ...

$ volatile.acidity : num 0.7 0.88 0.76 0.28 0.7 0.66 0.6 0.65 0.58 0.5 ...

$ citric.acid : num 0 0 0.04 0.56 0 0 0.06 0 0.02 0.36 ...

$ residual.sugar : num 1.9 2.6 2.3 1.9 1.9 1.8 1.6 1.2 2 6.1 ...

$ chlorides : num 0.076 0.098 0.092 0.075 0.076 0.075 0.069 0.065 0.073 0.071 ...

$ free.sulfur.dioxide : num 11 25 15 17 11 13 15 15 9 17 ...

$ total.sulfur.dioxide: num 34 67 54 60 34 40 59 21 18 102 ...

$ density : num 0.998 0.997 0.997 0.998 0.998 ...

$ pH : num 3.51 3.2 3.26 3.16 3.51 3.51 3.3 3.39 3.36 3.35 ...

$ sulphates : num 0.56 0.68 0.65 0.58 0.56 0.56 0.46 0.47 0.57 0.8 ...

$ alcohol : num 9.4 9.8 9.8 9.8 9.4 9.4 9.4 10 9.5 10.5 ...

$ quality : int 5 5 5 6 5 5 5 7 7 5 ...

Combine both red and white wine datasets.

wine_data <- rbind(white_wine, red_wine)

The summary function also provides quick insight into numerical data.

summary(wine_data)

fixed.acidity volatile.acidity citric.acid residual.sugar

Min. : 3.800 Min. :0.0800 Min. :0.0000 Min. : 0.600

1st Qu.: 6.400 1st Qu.:0.2300 1st Qu.:0.2500 1st Qu.: 1.800

Median : 7.000 Median :0.2900 Median :0.3100 Median : 3.000

Mean : 7.215 Mean :0.3397 Mean :0.3186 Mean : 5.443

3rd Qu.: 7.700 3rd Qu.:0.4000 3rd Qu.:0.3900 3rd Qu.: 8.100

Max. :15.900 Max. :1.5800 Max. :1.6600 Max. :65.800

chlorides free.sulfur.dioxide total.sulfur.dioxide

Min. :0.00900 Min. : 1.00 Min. : 6.0

1st Qu.:0.03800 1st Qu.: 17.00 1st Qu.: 77.0

Median :0.04700 Median : 29.00 Median :118.0

Mean :0.05603 Mean : 30.53 Mean :115.7

3rd Qu.:0.06500 3rd Qu.: 41.00 3rd Qu.:156.0

Max. :0.61100 Max. :289.00 Max. :440.0

density pH sulphates alcohol

Min. :0.9871 Min. :2.720 Min. :0.2200 Min. : 8.00

1st Qu.:0.9923 1st Qu.:3.110 1st Qu.:0.4300 1st Qu.: 9.50

Median :0.9949 Median :3.210 Median :0.5100 Median :10.30

Mean :0.9947 Mean :3.219 Mean :0.5313 Mean :10.49

3rd Qu.:0.9970 3rd Qu.:3.320 3rd Qu.:0.6000 3rd Qu.:11.30

Max. :1.0390 Max. :4.010 Max. :2.0000 Max. :14.90

quality

Min. :3.000

1st Qu.:5.000

Median :6.000

Mean :5.818

3rd Qu.:6.000

Max. :9.000

Check for NA values using the anyNA function.

anyNA(wine_data)

[1] FALSE

There are no missing values in the data.

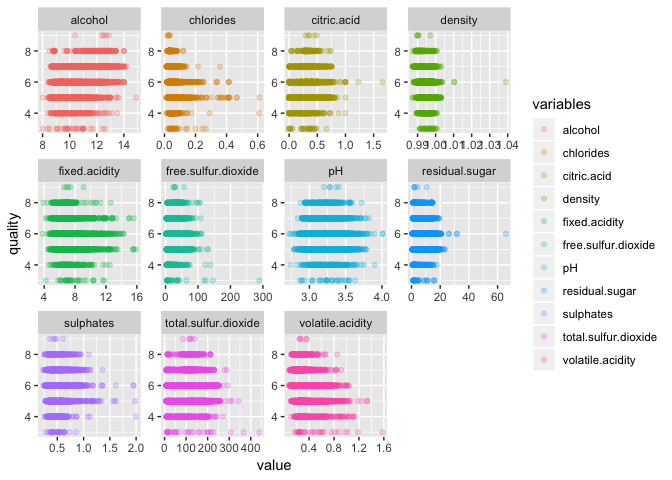

Plot each variable against “quality” in a matrix to visualize the data. The code below was written using the pipe function %>% from (Dplyr)[https://dplyr.tidyverse.org] and is especially useful for writing clean looking code.

wine_data %>%

gather(-quality, key = "variables", value = "value") %>%

ggplot(aes(x = value, y = quality, color = variables)) +

geom_point(alpha = 1/4) +

facet_wrap(~ variables, scales = "free") +

scale_fill_brewer(palette = "Set3",

name = "variables")

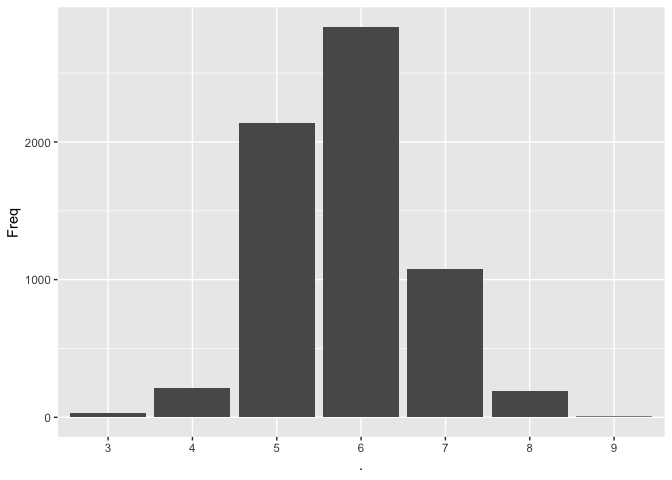

Visualize the data to see the distribution of the various wine qualities.

wine_data$quality %>% table() %>%

as.data.frame() %>%

ggplot(aes(x = ., y = Freq)) +

geom_bar(stat = "identity")

Get the table counts for the number of observations for each quality of wine.

wine_data$quality %>% table()

3 4 5 6 7 8 9

30 216 2138 2836 1079 193 5

Based on the table above, wine qualities of three and nine only make up 0.54% of all the observations. Because of this, it may be better to filter out these observations as the model will not have sufficient data to train on in order to accurately classify them. Therefore, the project will focus on classifying wine qualities ranging from four to eight.

Filter out any observations with wine qualities of three or nine.

wine_data <- wine_data %>%

filter(quality > 3 & quality < 9)

# Check to make sure observations were removed

unique(wine_data$quality)

[1] 6 5 7 8 4

Support Vector Machines assume the data is within a standard range of 0 to 1. Therefore, SVMs require data to be normalized prior to training the model. The custom function below normalizes data.

# Function to normalize the data

normalize <- function(x) {

return((x - min(x)) / (max(x) - min(x)))

}

# Remove rownames from the dataframe

row.names(wine_data) <- c()

wine_data_norm <- data.frame(lapply(wine_data, normalize))

# Check data to make sure variables were normalized

str(wine_data_norm)

'data.frame': 6462 obs. of 12 variables:

$ fixed.acidity : num 0.264 0.207 0.355 0.281 0.281 ...

$ volatile.acidity : num 0.152 0.176 0.16 0.12 0.12 0.16 0.192 0.152 0.176 0.112 ...

$ citric.acid : num 0.217 0.205 0.241 0.193 0.193 ...

$ residual.sugar : num 0.3083 0.0153 0.0966 0.1212 0.1212 ...

$ chlorides : num 0.0598 0.0664 0.0681 0.0814 0.0814 ...

$ free.sulfur.dioxide : num 0.32 0.0945 0.2109 0.3345 0.3345 ...

$ total.sulfur.dioxide: num 0.485 0.373 0.269 0.533 0.533 ...

$ density : num 0.268 0.133 0.154 0.164 0.164 ...

$ pH : num 0.217 0.45 0.419 0.364 0.364 ...

$ sulphates : num 0.129 0.152 0.124 0.101 0.101 ...

$ alcohol : num 0.116 0.217 0.304 0.275 0.275 ...

$ quality : num 0.5 0.5 0.5 0.5 0.5 0.5 0.5 0.5 0.5 0.5 ...

# Confirm the data has been normalized and that there are still only 5 qualities of wine

unique(wine_data_norm$quality)

[1] 0.50 0.25 0.75 1.00 0.00

Split the data into training, validation, and test datasets using random sampling.

# Set seed for duplication purposes

set.seed(123)

# Randomly sample and split the data

ss <- sample(1:3,

size=nrow(wine_data_norm),

replace=TRUE,

prob=c(0.6,0.2,0.2))

train <- wine_data[ss==1,]

validation <- wine_data[ss==2,]

test <- wine_data[ss==3,]

# Datasets with normalized observations

train_norm <- wine_data_norm[ss==1,]

validation_norm <- wine_data_norm[ss==2,]

test_norm <- wine_data_norm[ss==3,]

Step 3: Train the SVM model

Start with a simple linear SVM.

# Begin training with a simple linear SVM

quality_classifier <- ksvm(quality ~.,

data = train_norm,

kernel = "vanilladot")

## Setting default kernel parameters

print(quality_classifier)

Support Vector Machine object of class "ksvm"

SV type: eps-svr (regression)

parameter : epsilon = 0.1 cost C = 1

Linear (vanilla) kernel function.

Number of Support Vectors : 3518

Objective Function Value : -2172.043

Training error : 0.698757

In order to convert the normalized quality values back to it’s original scale (1-10), it will be useful to create a function that can be called to convert each predicted value to back to its respected quality value.

round_predictions <- function(x) {

if(x >= 0 & x <= 0.125) {

x = 4

} else if (x > 0.125 & x <= 0.375) {

x = 5

} else if (x > 0.375 & x <= 0.625) {

x = 6

} else if (x > 0.625 & x <= 0.875) {

x = 7

} else if (x > 0.875 & x <= 1) {

x = 8

} else if (x < 0) { # Sometimes the model may output negative values, in this case set it equal to a quality of 4

x = 4

} else if (x > 1.0) { # Sometimes the model may output values greater than 1, in this case set it equal to a quality of 8

x = 8

}

}

Using the trained simple linear SVM model, apply the model to the normalized validation dataset to check the accuracy of the model.

# Normalized validation set predictions

pred_validation <- predict(quality_classifier, validation_norm)

# Convert the predictions back to integers and store the predicted values

pred_validation <- sapply(pred_validation, round_predictions)

# Accuracy of the model

mean(pred_validation == validation$quality)

[1] 0.5399061

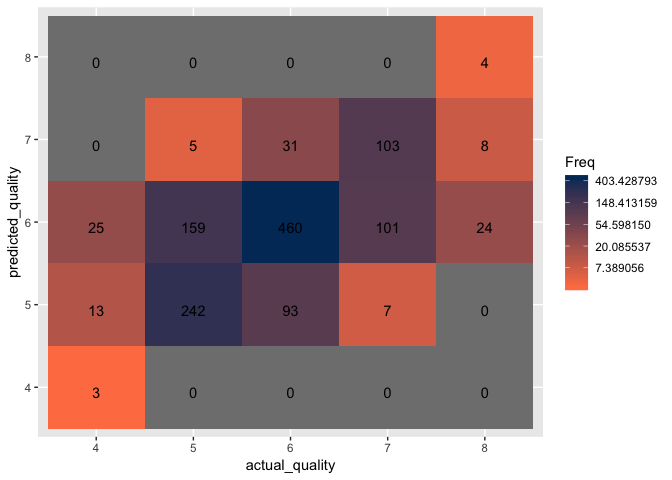

The simple linear SVM results in 54% accuracy.

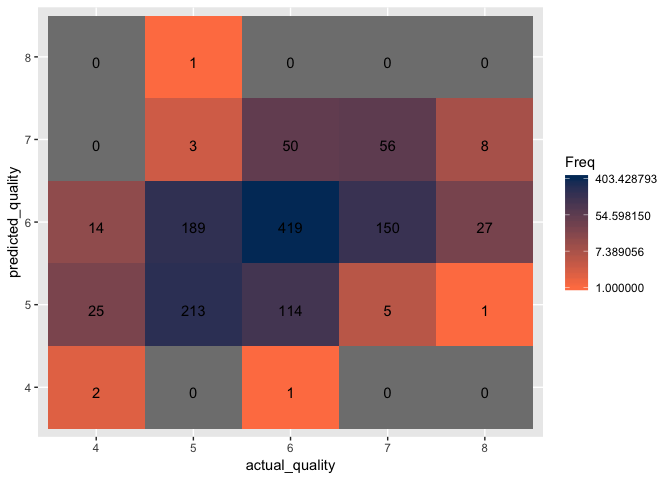

Create a confusion matrix to visualize the classification accuracy.

validation_results <- data.frame(cbind(validation$quality, pred_validation))

# Change the column names of the table

names(validation_results) <- c("actual_quality", "predicted_quality")

# Remove rownames

rownames(validation_results) <- c()

# Convert predicted and actual results from numerical to factors

validation_results$actual_quality <- factor(validation_results$actual_quality, levels = c("4", "5", "6", "7", "8"))

validation_results$predicted_quality <- factor(validation_results$predicted_quality, levels = c("4", "5", "6", "7", "8"))

confusion_matrix <- as.data.frame(table(validation_results$actual_quality, validation_results$predicted_quality))

confusion_matrix <- validation_results %>%

table() %>%

as.data.frame()

ggplot(data = confusion_matrix,

mapping = aes(x = actual_quality,

y = predicted_quality)) +

geom_tile(aes(fill = Freq)) +

geom_text(aes(label = sprintf("%1.0f", Freq)), vjust = 1) +

scale_fill_gradient(low = "#ff7f50",

high = "#003767",

trans = "log")

Step 4: Improve upon the model by implementing different kernels and fine-tuning the parameters

Because the data consists of multiple variables, a simple linear SVM may not result in the most accurate model. To try and improve the model, an RBF kernel with default parameters can be attempted next.

# RBF kernel SVM with default parameters

RBF_classifier <- svm(quality ~ .,

data = train_norm,

method = "C-classification",

kernel = "radial")

# Print out the parameters of cost and gamma from the updated algorithm

print(RBF_classifier)

Call:

svm(formula = quality ~ ., data = train_norm, method = "C-classification",

kernel = "radial")

Parameters:

SVM-Type: eps-regression

SVM-Kernel: radial

cost: 1

gamma: 0.09090909

epsilon: 0.1

Number of Support Vectors: 3329

Apply the new SVM model to the normalized validation dataset to check the accuracy of the model.

# Normalized validation dataset predictions

pred_validation <- predict(RBF_classifier, validation_norm)

# Convert the predictions back to integers and store the predicted values

pred_validation <- sapply(pred_validation, round_predictions)

# Accuracy of the model

mean(pred_validation == validation$quality)

[1] 0.5821596

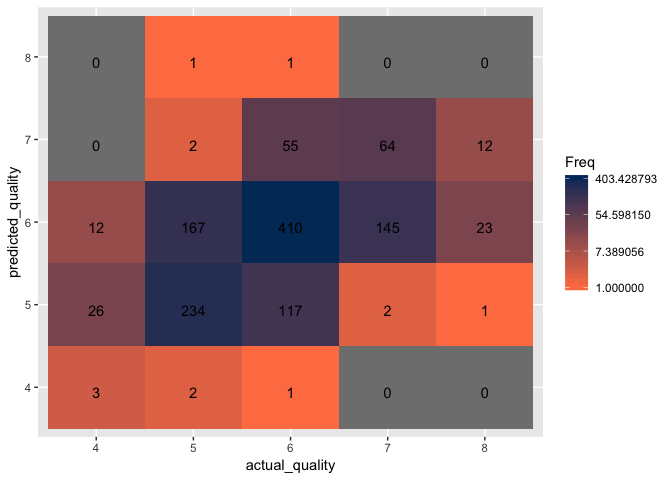

The RBF SVM model with default parameters results in 58.2% accuracy, an increase of 4.2% from the simple linear SVM.

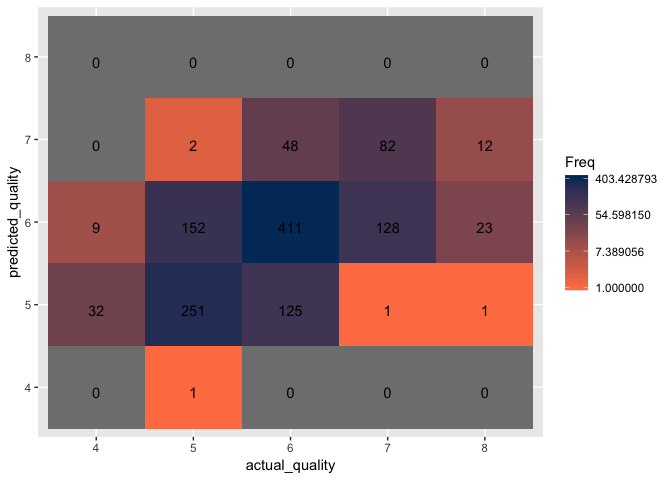

Create a confusion matrix to visualize the classification accuracy.

validation_results <- data.frame(cbind(validation$quality, pred_validation))

# Change the column names of the table

names(validation_results) <- c("actual_quality", "predicted_quality")

# Remove rownames

rownames(validation_results) <- c()

# Convert predicted and actual results from numerical to factors

validation_results$actual_quality <- factor(validation_results$actual_quality, levels = c("4", "5", "6", "7", "8"))

validation_results$predicted_quality <- factor(validation_results$predicted_quality, levels = c("4", "5", "6", "7", "8"))

confusion_matrix <- as.data.frame(table(validation_results$actual_quality, validation_results$predicted_quality))

confusion_matrix <- validation_results %>%

table() %>%

as.data.frame()

ggplot(data = confusion_matrix,

mapping = aes(x = actual_quality,

y = predicted_quality)) +

geom_tile(aes(fill = Freq)) +

geom_text(aes(label = sprintf("%1.0f", Freq)), vjust = 1) +

scale_fill_gradient(low = "#ff7f50",

high = "#003767",

trans = "log")

Lets try to tune and improve upon the RBF Kernel model by searching for the optimal parameters by using the tune.svm function.

# Obtain the column number of the quality variable

typeColNum <- grep("quality", names(wine_data))

# Find the optimal RBF parameters

RBF_tune <- tune.svm(x = train_norm[, -typeColNum],

y = train_norm[, typeColNum],

gamma = c(0.5, 1),

cost = c(1, 2),

epsilon = c(0.1, 0.2),

kernel = "radial")

# Print out the parameters of cost and gamma from the updated algorithm

RBF_tune$best.parameters$gamma

[1] 1

RBF_tune$best.parameters$cost

[1] 2

RBF_tune$best.parameters$epsilon

[1] 0.2

Using the updated parameters for cost and gamma obtained from the tune.svm function, train the SVM model on the train dataset.

tuned_RBF_classifier <- svm(quality ~ .,

data = train_norm,

method = "C-classification",

kernel = "radial",

cost = RBF_tune$best.parameters$cost,

gamma = RBF_tune$best.parameters$gamma,

epsilon = RBF_tune$best.parameters$epsilon)

Apply the SVM model to the validation dataset to check the accuracy of the model

# Validation dataset predictions

pred_validation <- predict(tuned_RBF_classifier, validation_norm)

# Convert the predictions back to integers and store the predicted values

pred_validation <- sapply(pred_validation, round_predictions)

# Accuracy of the model

mean(pred_validation == validation$quality)

[1] 0.6353678

The RBF SVM model with optimized parameters results in 61.2% accuracy, an increase of 3% from the default RBF SVM model.

Create a confusion matrix to visualize the classification accuracy.

validation_results <- data.frame(cbind(validation$quality, pred_validation))

# Change the column names of the table

names(validation_results) <- c("actual_quality", "predicted_quality")

# Remove rownames

rownames(validation_results) <- c()

# Convert predicted and actual results from numerical to factors

validation_results$actual_quality <- factor(validation_results$actual_quality, levels = c("4", "5", "6", "7", "8"))

validation_results$predicted_quality <- factor(validation_results$predicted_quality, levels = c("4", "5", "6", "7", "8"))

confusion_matrix <- as.data.frame(table(validation_results$actual_quality, validation_results$predicted_quality))

confusion_matrix <- validation_results %>%

table() %>%

as.data.frame()

ggplot(data = confusion_matrix,

mapping = aes(x = actual_quality,

y = predicted_quality)) +

geom_tile(aes(fill = Freq)) +

geom_text(aes(label = sprintf("%1.0f", Freq)), vjust = 1) +

scale_fill_gradient(low = "#ff7f50",

high = "#003767",

trans = "log")

Let’s experiment with a different variation of the SVM model by using the polynomial kernel and optimizing the parameters using the tune.svm function. It is best to only optimize three parameters at once as increasing the parameters may result in extended or indefinite run times. Once a few parameters have been optimized, attempt to optimize the rest.

# Obtain the best parameters for polynomial type kernel for the SVM model

polynomial_tune <- tune.svm(x = train_norm[, -typeColNum],

y = train_norm[, typeColNum],

cost = c(0.1, 1),

coef0 = c(0.1, 1, 2),

degree = c(2, 3),

epsilon = 0.1,

gamma = 0.1,

kernel = "polynomial")

# Using the updated parameters for coef0 and degree obtained from the tune.svm function, train the SVM model on the train dataset

tuned_polynomial_classifier <- svm(quality ~ .,

data = train_norm,

method = "C-classification",

kernel = "polynomial",

cost = polynomial_tune$best.parameters$cost,

coef0 = polynomial_tune$best.parameters$coef0,

degree = polynomial_tune$best.parameters$degree,

epsilon = polynomial_tune$best.parameters$epsilon,

gamma = polynomial_tune$best.parameters$gamma)

# Validation set predictions

pred_validation <-predict(tuned_polynomial_classifier, validation_norm)

# Convert the predictions back to integers and store the predicted values

pred_validation <- sapply(pred_validation, round_predictions)

# Accuracy of the model

mean(pred_validation == validation$quality)

## [1] 0.556338

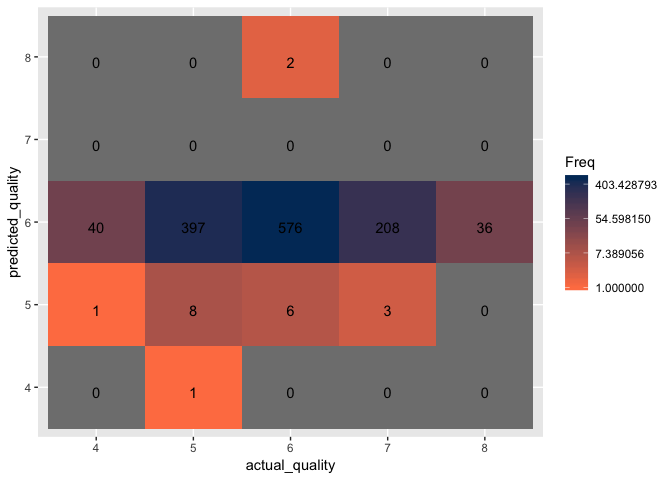

The polynomial SVM model with optimized parameters results in 55.6% accuracy, a decrease of 4.6% from the optimized RBF SVM model.

Create a confusion matrix to visualize the classification accuracy.

validation_results <- data.frame(cbind(validation$quality, pred_validation))

# Change the column names of the table

names(validation_results) <- c("actual_quality", "predicted_quality")

# Remove rownames

rownames(validation_results) <- c()

# Convert predicted and actual results from numerical to factors

validation_results$actual_quality <- factor(validation_results$actual_quality, levels = c("4", "5", "6", "7", "8"))

validation_results$predicted_quality <- factor(validation_results$predicted_quality, levels = c("4", "5", "6", "7", "8"))

confusion_matrix <- as.data.frame(table(validation_results$actual_quality, validation_results$predicted_quality))

confusion_matrix <- validation_results %>%

table() %>%

as.data.frame()

ggplot(data = confusion_matrix,

mapping = aes(x = actual_quality,

y = predicted_quality)) +

geom_tile(aes(fill = Freq)) +

geom_text(aes(label = sprintf("%1.0f", Freq)), vjust = 1) +

scale_fill_gradient(low = "#ff7f50",

high = "#003767",

trans = "log")

To experiment further with one last SVM model, we’ll use the Sigmoid Kernel SVM, and fine tune the parameters as well.

# Obtain the best parameters for polynomial type kernel for the SVM model

sigmoid_tune <- tune.svm(x = train_norm[, -typeColNum],

y = train_norm[, typeColNum],

gamma = c(0.01, 0.1, 1),

coef0 = c(1, 5),

cost = 3,

epsilon = 0.2,

kernel = "sigmoid")

# Using the updated parameters for cost, gamma, coef0, and degree obtained from the tune.svm function, train the SVM model on the train dataset

tuned_sigmoid_classifier <- svm(quality ~ .,

data = train_norm,

method = "C-classification",

kernel = "sigmoid",

gamma = sigmoid_tune$best.parameters$gamma,

coef0 = sigmoid_tune$best.parameters$coef0,

cost = sigmoid_tune$best.parameters$cost,

epsilon = sigmoid_tune$best.parameters$epsilon)

# Validation set predictions

pred_validation <- predict(tuned_sigmoid_classifier, validation_norm)

# Store the predicted values

pred_validation <- sapply(pred_validation, round_predictions)

# Accuracy of the model

mean(pred_validation == validation$quality)

[1] 0.456964

The sigmoid SVM model with optimized parameters results in 45.7% accuracy, a substantial decrease of 15.5% from the optimized RBF SVM model.

Create a confusion matrix to visualize the classification accuracy.

validation_results <- data.frame(cbind(validation$quality, pred_validation))

# Change the column names of the table

names(validation_results) <- c("actual_quality", "predicted_quality")

# Remove rownames

rownames(validation_results) <- c()

# Convert predicted and actual results from numerical to factors

validation_results$actual_quality <- factor(validation_results$actual_quality, levels = c("4", "5", "6", "7", "8"))

validation_results$predicted_quality <- factor(validation_results$predicted_quality, levels = c("4", "5", "6", "7", "8"))

confusion_matrix <- as.data.frame(table(validation_results$actual_quality, validation_results$predicted_quality))

confusion_matrix <- validation_results %>%

table() %>%

as.data.frame()

ggplot(data = confusion_matrix,

mapping = aes(x = actual_quality,

y = predicted_quality)) +

geom_tile(aes(fill = Freq)) +

geom_text(aes(label = sprintf("%1.0f", Freq)), vjust = 1) +

scale_fill_gradient(low = "#ff7f50",

high = "#003767",

trans = "log")

Out of the three optimized models, the optimized RBF model resulted in the highest accuracy at 61.2%. However, with the accuracy maxing out just above 60%, it is clear that SVM models are either not the best classification method for this project or the data is simply too “noisy” and “non-informative”.

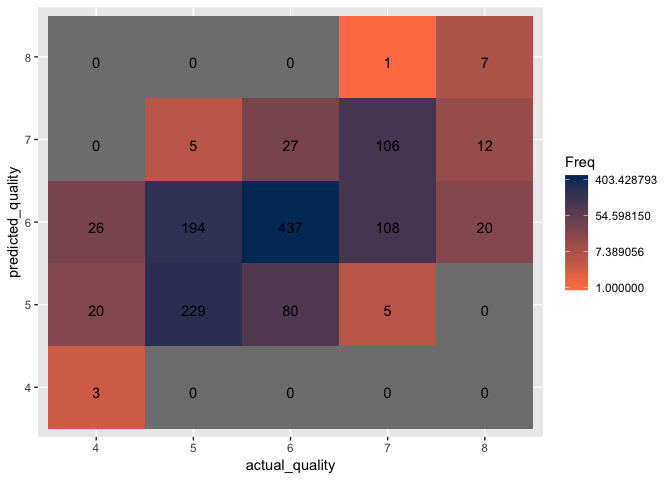

Step 5: Apply the best performing model to the test dataset

Although neither of the models performed well, we will finish the project by applying the best model discovered. Using the optimized parameters for cost, gamma, and epsilon obtained from the tune.svm function, we will apply the RBF Kernel model to the test dataset.

# Testdataset predictions

pred_test <- predict(tuned_RBF_classifier, test_norm)

# Convert the predictions back to integers and store the predicted values

pred_test <- sapply(pred_test, round_predictions)

# Accuracy of the model

mean(pred_test == test$quality)

[1] 0.6109375

The final result is 61.1% accuracy

Create a confusion matrix with statistics

test_results <- data.frame(cbind(test$quality, pred_test))

names(test_results) <- c("actual_quality", "predicted_quality")

rownames(test_results) <- c()

test_results$actual_quality <- factor(test_results$actual_quality, levels = c("4", "5", "6", "7", "8"))

test_results$predicted_quality <- factor(test_results$predicted_quality, levels = c("4", "5", "6", "7", "8"))

str(test_results)

'data.frame': 1280 obs. of 2 variables:

$ actual_quality : Factor w/ 5 levels "4","5","6","7",..: 3 2 4 5 3 3 3 3 2 4 ...

$ predicted_quality: Factor w/ 5 levels "4","5","6","7",..: 3 3 3 4 2 3 3 3 2 3 ...

Let’s create a confusion Matrix and compare actualy quality vs predicted quality.

confusionMatrix(test_results$actual_quality, test_results$predicted_quality)

Confusion Matrix and Statistics

Reference

Prediction 4 5 6 7 8

4 3 20 26 0 0

5 0 229 194 5 0

6 0 80 437 27 0

7 0 5 108 106 1

8 0 0 20 12 7

Overall Statistics

Accuracy : 0.6109

95% CI : (0.5836, 0.6378)

No Information Rate : 0.6133

P-Value [Acc > NIR] : 0.5804

Kappa : 0.3841

Mcnemar's Test P-Value : NA

Statistics by Class:

Class: 4 Class: 5 Class: 6 Class: 7 Class: 8

Sensitivity 1.000000 0.6856 0.5567 0.70667 0.875000

Specificity 0.963978 0.7896 0.7838 0.89912 0.974843

Pos Pred Value 0.061224 0.5350 0.8033 0.48182 0.179487

Neg Pred Value 1.000000 0.8768 0.5272 0.95849 0.999194

Prevalence 0.002344 0.2609 0.6133 0.11719 0.006250

Detection Rate 0.002344 0.1789 0.3414 0.08281 0.005469

Detection Prevalence 0.038281 0.3344 0.4250 0.17188 0.030469

Balanced Accuracy 0.981989 0.7376 0.6703 0.80289 0.924921

Create a confusion matrix to visualize the classification accuracy.

confusion_matrix <- as.data.frame(table(test_results$actual_quality, test_results$predicted_quality))

confusion_matrix <- test_results %>%

table() %>%

as.data.frame()

ggplot(data = confusion_matrix,

mapping = aes(x = actual_quality,

y = predicted_quality)) +

geom_tile(aes(fill = Freq)) +

geom_text(aes(label = sprintf("%1.0f", Freq)), vjust = 1) +

scale_fill_gradient(low = "#ff7f50",

high = "#003767",

trans = "log")

Conclusion:

Upon examining the visualization of the confusion matrix, it is clear that model excelled only at classifying wines with a quality of 6 with an accuracy rate of 75.4% despite having removed quality three and nine wines. The model struggles to classify all other qualities of wine with all others having an accuracy rate below 63%. Based on prior experience working with classification datasets, the problem appears to stem with the data either being too noisy, non-informative, or a combination of both. It is likely that the physiochemical properties of the various wines provide no insight into the quality of the wine. Another problem that arises with the dataset is there is no clear scientific methodology for classifying and rating the qualities of the wines. This information is crucial as there is no way to verify the reasons behind each rating and whether the reasons remain consistent with each wine. Moving forward with this project would require information on how the rating system works and possibly introducing further data such as the what grapes were used, the age of the wine, and how the wine was distilled and stored.

Regardless of the results, this was a fun project that demonstrates how widely applicable data science and machine learning is. Careful not to get too drunk on data and information though!